‘Once, during Prohibition, I was forced to live for days on nothing but food and water.’

W.C. Fields

Baku, home (allegedly) of the buy-one-get-one-free brothel: the British Airways flight from London was two-thirds full and had three female passengers. Most of the men seemed to be travelling alone and were, presumably, working in the well-paid oil industry, which generates vast wealth for a select few in Azerbaijan and beyond. One can readily imagine that the world’s oldest profession finds rich pickings in such a place and perhaps my friend’s anecdote is accurate. But I’m afraid I don’t have any data to back up this hunch.

I was met at the hotel by ‘Ishmael’, an Iranian friend whom I introduced in a previous post. Ishmael had arrived earlier in the day, meeting up with a friend in Baku, and had already eaten dinner but he had solicitously brought dates and nuts for me, presumably in case I couldn’t make it to the dining room without fainting from hunger. Unlikely, since my physique is a bit like a camel’s, except that my hump is ventral, not dorsal. I could go without food for several months without starving.

Because we wouldn’t be returning to Baku, instead crossing the land border into Iran at Astara, I’d had to hire a driver for the following few days. This turned out to be a happy necessity, for Elmar was an accommodating and good humoured chauffeur. In my experience, most drivers like to drive, whereas I prefer to stop, frequently. This has sometimes resulted in mutual frustration. Not so with Elmar. He had been advertised as ‘English-speaking’, which I think is a stretch. Azeri-speaking would be closer to the truth. Two English words that he did know, and used frequently, however, were ‘no problem’.

The drive from Baku to Lenkaran, in the south-east of Iran, was dull but fast and, when the thousands of nodding donkeys around Baku, pumping oil out of the land around the Caspian, had receded into the distance, I dozed. In the intervals when I was awake, Ishmael passed forward snacks – nuts, pumpkin seeds, fruits, what he called ‘plastic chocolates’, two varieties of dates, real chocolate – from a seemingly inexhaustible supply in the vast suitcase he had brought for the three-day trip.

From Lenkaran, which is on the Caspian coast and therefore below sea level (the Caspian is 28m below sea level), we took the road to Lerik, which is at 1,100m. Not very far out of Lenkaran, Ishmael shouted to Elmar to stop – he had caught a glimpse of snowdrop leaves. We investigated and found that a small population was indeed growing on a streamside bank, in someone’s citrus grove. Elmar stopped a passer-by and asked whether he knew the garden’s owner. Indeed he did and he proceeded to introduce us. The owner invited us into his garden and allowed me to photograph the snowdrops, a few of which were still flowering. Then he presented us with a delicious flatbread, baked in his own ‘tandir’ bread oven and a bag of oranges and mandarins from the garden. Would this sort of thing happen to an Azeri galanthophile driving around the UK? I doubt it.

The following day we explored this road again, more thoroughly. It rises through the fantastic Hyrcanian forests of the southern Caspian to the high elevation pastures of the Talysh Mountains. These forests are diverse, in both plant and animal species, largely because they constitute a ‘refugium’, to which species’ ranges contracted during the last glacial maximum, 20000 years ago, which never reached these parts. Some species that became extinct in other regions persisted here, along with ubiquitous species. Some have not recolonized their former large ranges and are now restricted to the refugia.

A large chunk of the Hyrcanian forest in Azerbaijan is protected as the Hyrcan National Park. There are few roads running into the protected area and none that go very high. We stopped at the park’s headquarters, to enquire whether there was any way at all that we could get up into the forest and the Park’s Director, Haji Aya Safarov (I hope I wrote his name down correctly) offered to show us around. Again I was humbled by the extraordinary Azeri hospitality.

Our time in Azerbaijan was up. Elmar took us to the frontier but, when we arrived, we found it closed. A heavy metal grille, six or seven metres wide, in the middle of which was a single, narrow, locked gate, held back a heaving, jostling mass of people, each struggling to inveigle his or her way through the scrum and get nearer to the gate. I am not especially tall but I was by some margin the tallest person in the crowd and, over the sea of heads, I could see through the bars a long concrete-floored shed, at the far end of which was another crowd, apparently waiting to be admitted into the border post proper.

Elmar made enquiries and established that the gate was opened only periodically and that only a certain, unspecified number of people would be admitted before it slammed shut again. We must sharpen our elbows, he implied, and be ready to make a dash for it, when the moment came. We waited and we waited. The hours ticked by and there was nothing to do except admire the ingenious manner in which some especially short women oozed through the crowd, to the front. I was reminded of a video I once saw of white blood cells gliding through apparently solid tissue like amoebae, to reach the source of an infection.

A fat policeman strutted about pompously, waving a truncheon above his head, impressing everyone with his great importance. Eventually, with obvious reluctance, he unlocked the narrow gate and the crowd surged forward, as though it were a single organism. The concept of an orderly queue is an alien in the Azeri mental landscape. The English, much mocked for their alleged fondness for queuing, have discovered that it is easier and quicker for a single file of human beings to pass through the eye of a needle than it is for a seething mass of humanity, to squeeze simultaneously into the kingdom of heaven (or, at least, Iran). I was borne forward, enjoying this very un-English experience hugely but others, particularly the elderly women being crushed against the metal barriers, appeared to be genuinely distressed. The policeman was shouting and waving his truncheon, and seemed to be on the point of using it, something reptilian flashing behind the small eyes, sunken in his fleshy face. Ishmael was urging me to elbow the small man beside me out of the way; the small man beside me was yanking on my rucksack to hold me back. For a while, it all went very banana republic.

Miraculously, we made it through and everyone was smiling again, except those wailing and gnashing their teeth behind the now locked gate, whence there was much pointless ululating and lamenting. Those of us privileged to have been admitted to the real queue now began again the process of trying by stealth to move closer to its head, where a sour-faced official was checking passports. As we shuffled forward, we watched people returning in the opposite direction, from day trips to Iran, where most goods are much cheaper than in Azerbaijan. One woman, balancing on her head a huge metal dish, filled with foodstuffs and cleaning products, caused much mirth in the queue.

For various reasons my Azeri visa was in one of my two British passports and my Iranian visa in the other. This unusual state of affairs resulted in much consultation among the numerous officials milling around but I was, without much further ado, permitted to leave Azerbaijan. Entering Iran was not quite so straightforward. Ishmael, delighted to be (almost) back in his home country, engaged the border official in conversation. This was, I think, a mistake. The official was entertained by the US visa in my passport, showing it to all his colleagues. Not knowing what to do with a British passport, he shuffled it up the chain to an equally clueless superior. The superior questioned a now visibly rattled Ishmael closely, in Farsi, before instructing the two of us to follow him to an upstairs office. There we were told, not discourteously, to sit and there we waited, while various police officers came and went, telephone calls were made, passports were photocopied and scanned and details of our intended itinerary in Iran written out longhand. An interesting obsession with my father’s name revealed itself. What possible interest could the Iranian state have in knowing that my father’s name was – he died 17 years ago – Aubrey? It would amuse him to know that a ghostly electronic echo of his existence now resides in a data centre somewhere in Iran. I could not, of course, understand anything of what was being said but the body language appeared unthreatening and there was much nervous laughter and smiling, on all sides. A waiter brought us tea.

It was fascinating to watch the operation of an Iranian border police office. On each desk was a small pile of cardboard files, containing papers, photographs and passports. These were repeatedly moved from one desk to another, papers being removed from certain files and reinserted into others. Occasionally one of the police officers would remove either a red or a black ink pad from a drawer and carefully stamp one of the papers. Then he would replace the ink pad in the drawer and move the file to a different desk. Sheets of paper were precisely cut into two and these smaller pieces of paper were fed into a photocopier, the resulting passport copies being distributed among the various files.

All this activity took place at a leisurely pace that suggested people with a lot of time on their hands and very little of value with which to fill it. Rubber stamps, ink pads, paper clips, staplers, cardboard folders: these are the seemingly innocuous tools of the bureaucrat’s trade and with them, if we let him, he will eventually incarcerate us all in a prison sealed, in triplicate, with red tape.

I was evidently the most interesting thing that had happened here for some while and many people came into the room to examine the Englishman. It turned out later (according to Ishmael) that I was the first person with a British passport that any of the officers had ever seen. I find this hard to credit but I have rarely been the object of such intense curiosity and scrutiny. According to Ishmael, the police also told him that I must be a very dangerous man and that he should on no account associate with me. I have been accused of being many bad things, often accurately, but dangerous? Then it occurred to me that, in a theocracy, anyone who thinks for himself is dangerous.

After two hours it was eventually agreed that I could enter Iran but first I must have my fingerprints taken. To this end, we had to report to the nearest police station. We were accompanied there by a young, tall soldier, who seemed as unsure of himself as we were. I was escorted into the office of the fingerprint man, who was sitting at a desk across which were strewn sheets of paper, covered with fingerprints. He was examining one set, through a desk magnifying glass and, just for a moment, I was exceedingly grateful to be a British citizen.

My fingerprints were taken on a device that looked alarmingly like a thumbscrew. This was not a simple exercise. Every digit, on both hands, was carefully rolled in thick, black ink and meticulously pressed onto its designated space on a pre-printed sheet. Twice. Then, five hours after we had been scheduled to enter Iran, my passport was returned, with a smile and I was back in Iran. I am now one of a select group of people with police records in both the United States of America and the Islamic Republic of Iran, an achievement of which I am unabashedly proud. As I have pointed out previously on this blog, those two great nations share much more than either would care to admit.

It is tempting to excuse the police who held my friend and me at the frontier for hours, despite the fact that he is an Iranian citizen and I had a perfectly valid visa and was being met at the border, as is required for British and American citizens, by an authorised tour guide. After all, they were just doing their jobs, weren’t they? ‘I was just doing my job’ has, however, been the chosen excuse of the perpetrators of recent history’s vilest crimes of omission. Little acts of cowardice – bumping awkward decisions up the chain of blame; exercising limited power just because you can; recording everything, in case it should come in handy later* – collectively add up to complicity.

Waiting for us when we were free men again was Mostafa Selahi.

Since our first meeting, three months ago, Mostafa’s regard for the rules of the road appeared to have deteriorated from disregard to open contempt. As we headed west from Astara, it quickly became clear that he now viewed the injunction to drive on the right as fulfilling a purely advisory role, to be obeyed only when interesting plants or rock formations happened to be best viewed from that angle. Iranian roads have frequent speed bumps and Mostafa seemed to have interpreted the function of these obstacles as an invitation to depress the accelerator, not the brake. Ishmael and I teased him mercilessly about this, which seemed only to goad him into ever greater acts of virtuosity, in his attempt to get his decidedly reluctant Mitsubishi tank airborne. Our velocity varied between 20 kilometres per hour and a hair-raising 60, and was entirely uncorrelated with the quality of the road, the volume of traffic, the urgency with which Ishmael and I wanted to reach our next destination or – pah! – the speed limit. An unfortunate goat, grazing at the roadside, had the nonchalance permanently knocked out of it, when it unwisely decided to ignore the large vehicle bearing down at speed, its driver fully engaged in a disquisition on the cave systems of southern Iran. While attempting to fasten his seatbelt with the same hand that was controlling the steering wheel, Mostafa swerved wildly across the road directly towards a parked BMW. An involuntary squeal of unalloyed terror escaped my lips, which caused Mostafa to abandon his attempt to find the buckle and swerve equally violently to the opposite carriageway. He giggled and glanced heavenwards, raising a palm, as if to say ‘can’t I leave anything to you?’

It was (a few days later) in Tehran that Mostafa’s sublime indifference to the rights of all other forms of road-using life reached its apotheosis. He would aim the car at gaps in the traffic that would have caused a dieting ferret to stop and think twice. The traffic would miraculously part, like the waters of the Red Sea before Moses, often with inches to spare either side of the fenders. Into the breach we would sail, the outraged honking of horns Doppler-shifting into the distance.

‘E-ke-skeeeewze me!’ Mostapha would say, giggling.

Mostafa is a man of many parts. A sometime rabble-rouser, his family seriously pissed off both the last Shah and the current, post-revolution regime, quite an achievement, considering that the Shah and the Islamists were themselves mortal enemies. His only brother has been living in exile in Germany for more than 30 years. Now a retired geography teacher and part-time tour guide, he is the author of an authoritative book on the caves of Iran. He has also climbed all of the many peaks in the country higher than 3000m.

In the apartment of Mostafa’s wife, Nayer, I was shown a black-and-white photograph taken on their honeymoon. Nayer was 19 at the time and strikingly beautiful. Mostafa was 34 and he cut a dashing figure, slim, powerful, smiling cockily at the camera, his moustache black and luxuriant. Looking at the old man slumped opposite me in an armchair, with his rheumy eyes and deeply-etched face, his mind wandering as he slowly sipping heavily-sweetened tea, I could still recognise the bold, confident young mountaineer in the photograph.

‘In those days,’ said Mostafa wistfully, ‘I was rrreally hero.’

He still is.

The weather over the three days we spent in Iran was dreadful. Low cloud shrouded the mountains above 400 or 500 metres elevation. It takes a long time to get anywhere in Iran, a populous country with a road infrastructure not really capable of dealing with the volume of traffic. Bad weather and incessant traffic are not usually a mood-enhancing combination for me, but I was uncommonly happy. Ishmael and Mostafa were good travelling companions. Despite the weather, we saw some wonderful plants and dramatic scenery. I shall particularly treasure a photograph that Ishmael snapped, while I sat on a hillside, surrounded by thousands of Cyclamen elegans and smaller numbers of flowering Dog’s Tooth Violets, Erythronium caucasicum. Life doesn’t get better than this.

Ishmael had invited me to stay with his family in northern Iran on the penultimate night of my trip. I was highly honoured and gladly accepted. Ishmael’s mum was going to cook me kaleh pacheh, the boiled head and feet of a sheep. In Iran, this dish is usually eaten for breakfast but, with typical thoughtfulness, Ishmael enquired whether I wouldn’t rather have it for dinner? I’d rather have had it in the next life, but I didn’t say that.

It’s amazing how much food there is in a sheep’s head, if you eat everything except the bones. I had a generous bit each of ear, eye, tongue, brain, neck and stomach. The tongue was really rather delicious. But slurping up a slowly congealing eyeball is quite high on the list of things I hope never to do again.

I cannot pretend that I enjoyed the kaleh pacheh but I tried to eat it with every indication of enthusiasm and I hope I did a reasonable job of conveying my sincere appreciation of the privilege of having been invited to dine in an Iranian home.

To be honest, I usually find time spent in the company of people with whom I don’t share a common language trying, at best. But here I was surrounded by clever, funny, curious people, peppering me with questions about the UK and frankly answering my own, sometimes naïve, questions about Iran.

‘Why is it that I don’t hear the azan here all the time, as I do in Turkey?’ I asked.

‘We Shias only pray three times a day. With Sunnis, it’s five times.’

‘Are you orthodox?’ asked someone.

‘Me? Gosh, ha ha, no! I’m an atheist.’

For the first time, my hosts looked a little shifty.

‘A freethinker!’ someone said, after a pregnant pause. ‘It’s OK here, but please don’t say that in public. Tell people you are a Christian.’

But, of course, I won’t do that, unless I feel my life is in imminent danger, in which event I doubt whether faking a belief in God would postpone the inevitable for long. It is a tragedy that educated people in strict Muslim countries have no choice but to live deeply hypocritical lives. In private they drink alcohol, while foreswearing it in public. Behind closed doors they ignore the obligation to pray to a God in whom they do not really believe, while going through the motions in public. They laugh, while among friends, at the facile dogmas promulgated by their religious leaders, while paying public lip service.

In Iran, elementary school children are still taught to chant ‘Death to America! Death to Britain! Death to Israel!’ But the Iranians I met have nothing against British or American people, though they do seem to have a problem with Israel.

‘Once, during Prohibition, I was forced to live for days on nothing but food and water.’ I now know exactly how W.C. Fields felt. A correspondent recently told me that my public ‘pronouncements’ on alcohol meant that I couldn’t be ‘culturally sensitive’ in Iran. It’s this kind of half-witted thinking that led an anonymous Italian civil servant to cover nude sculptures in the Colosseum with boxes, out of consideration for the sensibilities of the visiting Iranian president, Hassan Rouhani. Incidentally, this decision was mocked almost as widely in Iran, where it was seen as unbearably patronising, as it was in Europe**.

Permit me tell you a story about cultural sensitivity.

The hotel at which we had stayed in Azerbaijan had a good restaurant. The first night we ate there, I ordered a bottle of local wine and asked my two (nominally Muslim) companions what they’d like to drink. Elmar requested a beer and Ishmael shared the wine with me. This performance was repeated on the next two evenings and gentle questioning revealed that alcohol is easily available in Iran but is very expensive, especially wine, which Ishmael enjoyed.

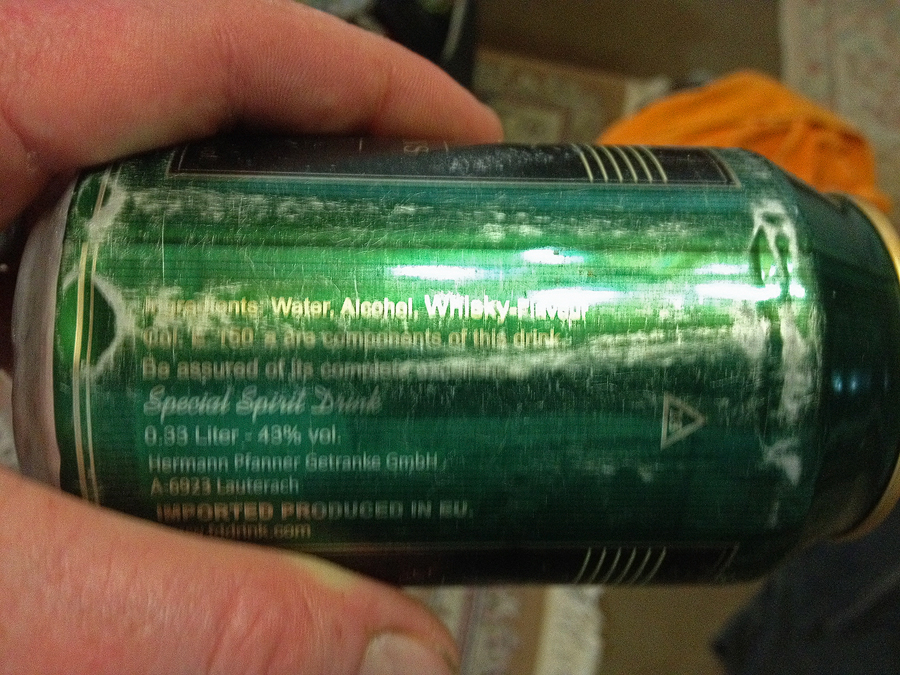

Ishmael evidently noticed my enthusiasm for alcohol and, unbeknownst to me, went to great lengths, and presumably expense, to obtain two cans of ‘whisky-flavoured beverage’, the chief ingredients of which were water and ethanol. These he placed in the fridge in the room that he gave up for me, the night I stayed in his home and, after the sheep’s head experience, he showed them to me. ‘Are these alright for you?’ he asked. I could have kissed him.

Real cultural sensitivity, as opposed to the fake variety that hides behind the fig leaf of political correctness, consists in treating strangers in a manner that both acknowledges their difference and accepts it. It involves refusing to attempt to impose your own values and beliefs on people who are different. Crucially, it also involves a steadfast refusal to pretend respect for views that, in fact, you hold in contempt or disregard. If Donald Trump becomes President of the USA, visitors to that country will not suddenly acquire a duty to become mysogynistic, homophobic, Mexican-hating, xenophobes, out of ‘respect’.

Ishmael was an exemplary host. He perceived a duty to understand my needs (actually my wants, for I’d have been perfectly content without the alcohol). He went far out of his way to see that they were satisfied, even when doing so required him to break local taboos.

I have, on an enormous pile of books waiting to be read, ‘Reading Lolita in Tehran’ by Azar Nafisi. I had thought of taking it to Iran with me, if only because I liked the idea of a blog post entitled ‘Reading ‘Reading Lolita in Tehran’ in Tehran’. But then Corinne, my wise, gorgeous and immensely forbearing partner in life and parenthood, gave me the second volume of Richard Dawkins’ autobiography, ‘Brief Candle in the Dark’ and I realised that this would make far more seditious reading than a book about a book club. After all, whereas the reading of child porn is not a direct threat to the theocracy, if Dawkins is right, then the Ayatollahs are wrong, about everything. So, in the evenings after we’d all retired to bed, I read the captivating life story of a man who’s candle has burned brightly indeed throughout my intellectual life. I’m betting against the Ayatollahs.

Actually, the book is not really an autobiography of Dawkins – we learn rather little about the man behind the books – but a beautifully framed window onto the bleeding edge of scientific and intellectual life in the last fifty years. For that reason, there are very few Muslims between its covers. Dawkins seems to know everyone and he tells some wonderful anecdotes. My favourite is a story about the Kenyan palaeontologist Richard Leakey, who was almost killed in a suspicious light aircraft crash, at the end of his highly successful tenure as Director of the Kenya Wildlife Service. Leakey survived but both his legs had to be amputated. Dawkins takes up the story.

After they were amputated in Cambridge he wanted, for sentimental reasons, to bury them in his beloved Kenya. He had to get permission to transport them, and bureaucracy insisted that this was possible only if he could produce a death certificate. He very reasonably argued that he wasn’t dead, and eventually the dundridges saw the justice of this and agreed. They stipulated, however, that he must take them in his hand luggage. Legs may not be checked in.

If it were in my power to extinguish one thing from our world it would not be religion, as many of my friends would guess, nor bureaucracy for I concede, reluctantly, that someone has to run the place. What I would like to abolish is dundridges – people who regard not thinking for yourself as one of the cardinal virtues – of exactly the sort who spend their days deciding that legs, whether attached or detatched, must travel carry-on.

* When I was interviewed by a policewoman in the USA, the interview was secretly recorded, obviously without my consent. This practice is perfectly legal in the state of West Virginia, as it is in Raqqa, but not anywhere where justice is respected. At the Iranian border, however illegitimate the questions, at least everything was in the open.

** For example, see http://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-35423028

Very interesting to read… Thanks for sharing!

I used to live in Tehran, but it’s been 4 years since I’ve moved to northern Iran (Guilan province). Its a privilege to see my country through the eyes of a foreign plantsman. I especially love those funny and quirky things you describe about Iranians 🙂

Hope you visit again soon. I’m eager to join you in a future plant hunt.

Best regards, Mohsen.

Thanks Moshen! The privilege was really mine. I enjoyed every minute of my time in Iran and long to return to see more of your country. Let’s hope that the politicians and the pandemic allow that in the years to come.