Having grown up on a self-imposed diet of Gerald Durrell’s nostalgic Corfu books, my prejudices about Albania were installed early and serviced regularly. Whereas Durrell’s Greece was light, civilised and endearing, Albania ‘brooded’ on the eastern horizon, ‘dark’ and ‘forbidding’, shrouded in clouds and populated by brigands.

In the early 1980s, when I was an adolescent, Albania was a pariah state, closed to outsiders and existing, like today’s North Korea, in a bizarre Stalinist bubble. Enver Hoxha, a WWII partisan hero, turned homicidal maniac, had been Albania’s dictator for nearly four decades, eventually becoming the sort of ghastly self-parody to which Kim Jong Il can still only aspire. Hoxha alienated first Tito’s Yugoslavia (too expansionist), then Khrushchev’s Russia (too revisionist) and finally Mao’s China (insufficiently on-message in inviting American politicians to visit), reducing Albanians from poverty to a state of abjection unique in Europe and in any country not at war. Hoxha died, the Berlin Wall fell, students rioted in Tirana and democracy, of a sort, came to Albania.

Very slowly, Albania has emerged from isolation. These days, you can get a British Airways scheduled flight from London to Tirana, enter the country without a visa, hire a car and drive yourself around. The people one meets are eager to solicit one’s opinion, evidently self-conscious about Albania’s image in the wider world. ‘What do you think of my country?’ they would ask, beaming with pleasure when I answered, truthfully, that I was loving every minute of my time in their country.

I had only a few days to explore and confined myself to the southern third of the country. I was, of course, in Albania in search of autumn-flowering snowdrops, and these were said to occur in the vicinity of Sarandë*. I had seen the lights of this town each evening from my cottage in Corfu, where I spent a week in late October and it made perfect sense that the snowdrops I found in Corfu would also occur across the narrow strait.

The town of Gjirokaster was my base for the first two nights. I had been drawn here by some lines in the guidebook, quoting Ismail Kadare, Albania’s only literary export.

It was a steep city, perhaps the steepest in the world, which had broken all the laws of town planning. Because of its steepness, it would come about that at the roof level of one house you would find the foundations of another; and certainly this was the only place in the world where if a passer-by fell, instead of sliding into a roadside ditch, he might end up on the roof of a tall house. This is something that drunkards knew better than anyone.

I liked the idea of a town in which I might inadvertently find myself sharing a roof, rather than a ditch, with fellow drinkers. In the event, my comfortable bed proved perfectly adequate but, having arrived after dark, I awoke early and looked out from my balcony over a sea of stone tiles to the snow-capped mountains to the east. Gjirokaster lies on the western flank of a broad, glacial valley, the fertile floor of which is intensively farmed. The climate is mild and the snow, which had fallen only the previous week, according to the hotel’s proprietor, had started to melt by the time I left.

Only a few of the roads in Albania are paved and maintained to a reasonable standard and these few are almost comically over-policed. Every few miles, bored policemen stand with radar guns, shooting fish in a barrel. The speed limit varies seemingly at random, with respect to the quality of the road, presumably with a view to maximising the revenue of the traffic cops. It is a miracle up there with the virgin birth of our Lord Jesus Christ himself that I wasn’t caught. Or perhaps it’s because I was driving a Skoda.

A small river, the Bistrica, runs from the ridge west of Gjirokaster to the sea at Sarandë. The limestone hillsides are covered with typical eastern Mediterranean garrigue, but the course of the river is marked out by deciduous oaks, Hop-Hornbeam and plane trees.

There was Ruscus aculeatus, ivy, Cyclamen hederifolium (almost finished flowering) and emerging Arum italicum foliage on the deeply shaded forest floor. The Bistrica runs more-or-less east to west and on the north-facing banks of the deeply cut river channel were lots of snowdrops many, to my slight surprise, still in full flower.

In Sarandë I ate delicious octopus for lunch and stared at Corfu trying, unsuccessfully, to pinpoint where I had stayed in October.

The best food I ate was on my first evening in Gjirokaster. The proprietor of the restaurant I chose took it upon himself to bring me a succession of small, delicious dishes. Fist, a yoghurty, oniony soup, flavoured with lashings of dill, tiny meatballs swimming in the broth. After that, byrek (filo pastry with any number of possible fillings) of two different types, one stuffed with spinach, the other with squash. On the side of this plate were two contrasting cheeses, one like mozzarella, but spiced with chilli, the other a crumbly goat’s cheese. I was ready to quit, but a dish of pork, peppers and more dill arrived, and somehow I rearranged my internal organs sufficiently to accommodate it. The Albanian red wine was outstandingly good. Several glasses of the local raki rounded off a fine evening. The bill came to about fifteen quid.

I very much like dining alone. I love to eat and, even more, I love to drink but, being a misanthrope, I dislike having to make conversation or having to moderate my consumption of either food or alcohol to suit the prejudices of dining companions. For company I dine with a good book, or I write up notes from the day’s travels.

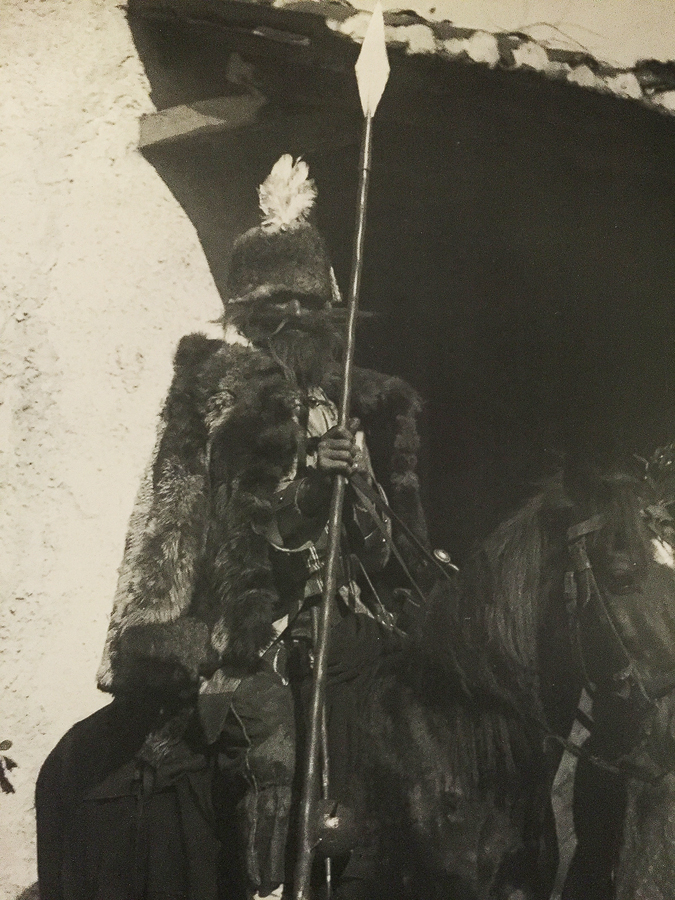

Often, as I scribble away, I’m asked whether I’m a journalist, which I always deny. But it’s too complicated, generally, to explain in pidgin English that I am travelling to see plants, especially when it’s late November and flowers are conspicuous by their absence. So, usually, I claim to be a photographer. On hearing this, the proprietor produced a large book of old black-and-white photographs which I browsed, at first out of politeness but then genuine curiosity, amazed at the extraordinary facial hair styles of Albanians past.

On my large scale map of Albania were marked numerous appealing minor roads but most of these turned out to be usable only by owners of a donkey or a tank. It was while attempting to go just a little bit further down one of these rutted tracks that a prolonged grinding of rock on metal came from underneath the hired Skoda (clearance about 15cm). This is not an uncommon experience when I’m driving in pursuit of snowdrops and I thought nothing of it until warning lights started to flash on the instrument panel and a quick inspection revealed a steady stream of oil running from a sump beneath the engine.

The Skoda limped on to the nearest garage, where extraordinarily helpful people arranged for a tow truck to take the car to the nearest repair shop, where a few layers of epoxy were applied to the hole in the sump and I went on my way. The whole incident delayed me by only three hours and I arrived in Berat, my next destination, in time for dinner and another bottle of that excellent wine.

Berat was my base for exploring the Osum river valley. South of Berat, the floodplain is broad and cultivated in strips, resembling an illustration from a history book of mediaeval farming techniques. Beyond Çorovode, however, the river’s gradient is steeper and it has cut a deep, sheer-sided canyon through the soft limestone. Though not much higher in elevation than Gjirokaster, the vegetation suggested a more continental climate. Cyclamen hederifolium grew under scrubby oaks with Helleborus cyclophyllus which, unusually among this group of hellebores, has semi-evergreen leaves. There are said to be snowdrops here too (Galanthus reginae-olgae, the same species that is flowering now near Sarandë) but here they flower in early spring, after the snow melts.

There was just time, on my final day in Albania, to drive the spectacular coast road – ambitiously labelled, presumably by the tourist board, the Albanian Riviera – that runs south from Vlorë, over the Llogara Pass to Sarandë, returning by the over-policed motorway to Tirana for my late flight back to London.

*Shuka, L, Malo, S & Tan, K (2011) New chorological data and floristic notes for Albania. Botanica Serbica 35 (2): 157-162.