Planning the snowdropathon has been an exercise in logistics that would have had the Fedex mainframe scratching its circuits in frustration. The dates around which snowdrop species flower in cultivation provide only the sketchiest of guides to corresponding dates in the wild. What’s more, every year is different and fluctuating patterns of rainfall and temperature can cause emergence dates to shift by weeks. Inevitably, the result is sometimes a busted flush, as with my attempt to see Galanthus transcaucasicus in Iran. Occasionally, however, the stars align and extreme snowdropping becomes a doddle.

I was in SW Turkey a little over a month ago, hoping to see early flowering Galanthus peshmenii but found that the sites where it occurs were bone dry and only a handful of plants had emerged at the highest elevation population I know.

Returning to the same valley, west of Kemer, on 23 November, I found a population of thousands of plants in spectacular flower, running like a seam of quartz along the north-facing slope of a steep-sided river valley. Here they were completely shaded from the blazing autumn sunshine, which had me sweating in my thin tee-shirt, as I clambered over the rounded limestone boulders of the river bed. Despite heavy recent rains, the river bed was almost dry. After the snow melts in spring, it will be flowing fast.

Having been invisible only five weeks previously, many of these plants had now already finished flowering (indeed, at the highest elevation site, all the plants were beginning to set seed). Enough late ones were in peak condition, however, to give a fine impression of the variation within the population.

The vegetation in these sites is dominated by pines, but magnificent plane trees mark out the courses of seasonal rivers and streams, often growing within the river bed. The understory is a rich mix of Cotinus coggyria, Bay (Laurus nobilis), Oleander (Nerium oleander), Myrtle (Myrtus communis), spiny, evergreen oaks (Quercus spp.) and other leafless, deciduous shrubs that defeated my improving but still woefully inadequate field botany. The spurge, Euphorbia characias and Butcher’s Broom (Ruscus aculeatus) are ubiquitous at low elevations, E. myrsinites replacing the former higher up. In the deep shade of the river bed grow numerous ferns, including great clumps of a Polypodium species, the new fronds startlingly vibrant against the white limestone. The infinitely variable leaves of Cyclamen maritimum, their flowers over, mingled with less frequent Cyclamen alpinum, which will flower in spring, the latter starting to appear only above about 500m elevation. A few plants of Crocus cancellatus subsp. lycius (plain C. lycius, according to some botanists) were flowering, on the same shady rocks as the Galanthus.

Galanthus peshmenii is known in cultivation only from a handful of collections, including one made in this very valley above Kemer, by Bob and Rannveig Wallis and another from the Greek island of Kastellorizo by Martyn Rix. The few named selections that have been made, including one or two with rather feeble green tips to the outer segments, have not yet been widely distributed.

In wild populations this species is, of course, as variable as any other snowdrop.

In stature G. peshmenii is rather small. The scapes (flower-bearing stalks) of a small sample I measured ranged between 10cm and 20cm but some plants, especially those growing in crevices in boulders, were even shorter, perhaps dwarfed by the conditions in which they grew. The flowers varied greatly in size, the outer segments measuring from less than a centimetre to 2.5cm in length. The combination of relatively large flowers and short scapes is rather pleasing, to my eye, creating an impression of a neat and vigorous plant. I fancy that the absence of leaves at flowering time further enhances the beauty of a clump of a single clone, focusing one’s attention on the pristine flowers.

Unlike the morphologically similar Galanthus reginae-olgae, G. peshmenii displays a noticeable tendency to form small clumps, by the offsetting of bulbs. Conversely, whereas the former species quite often produces two scapes per bulb, this appears to happen only rarely in G. peshmenii in the wild.

Having said that the leaves are absent at flowering time, I should note that this feature is also variable. In some cases the leaves had already emerged by several centimetres while the plants were in flower. Most plants that had finished flowering already had well-developed leaves. These will go on to become extraordinarily long – up to 40cm – hanging like seaweed from the rocks*. The leaf colour was noticeably glaucous (having a waxy, blueish bloom) or glaucescent (midway between glaucous and green). A prominent pale median stripe on the adaxial (upper) surface was present on all the plants I examined.

All snowdrop species have a single pair of leaves per bulb (leaving aside occasional freaks with three or more leaves). The manner in which the two leaves are pressed together at the point where they emerge from the sheath** – a feature referred to as their ‘vernation’ – is of some diagnostic value in separating species. The books say that in G. peshmenii the vernation is ‘applanate’, which is to say that the upper surfaces of the two leaves are pressed flat together at the neck of the bulb and the margins of the leaves are also flat. This broadly concurs with my observations but, in many specimens, the edges of the leaves, especially at their bases, were rolled back on themselves, in a manner that is referred to as ‘revolute’ or ‘subrevolute’, if you want to hedge your bets, which I do.

The outer segments are shaped like a concave paddle, with a short, but variable handle, the ‘claw’ of the segment.

The segments are widest near their apices but the edges are typically almost parallel for most of their length. The ends of the segments are often rather ‘square’, with a small, acuminate tip, which reflexes as the flower ages, creating the (false) impression that the outer segments possess a sinus. This shape, difficult to describe, gives the segments a distinctive, almost oblong outline, especially when the flowers are viewed from above.

A very small proportion of plants have small green markings towards the tip of the outer segments though, in all the cases I saw, this was distinctly subtle. Occasional mutants with four or five inner and outer segments were rarer still.

The inner segments are roughly triangular, narrowest at the base and have a distinctively small notch (sinus) at their apex. The green mark at the apex of the inner segment is typically V-shaped, diffuse and small, sometimes reduced to a pale green smudge or two dots either side of the sinus. Occasionally, however, the inner segment mark is larger, sometimes extending over most of the apical half of the segment and/or assuming a pleasing inverted heart shape.

Until I had had an opportunity to study both species carefully in the wild I would have said that flowering G. peshmenii and G. reginae-olgae are impossible to tell apart reliably, without knowledge of a plant’s provenance. The remarkable morphological similarity of these two species appears to be an interesting case of convergent evolution. Whereas G. reginae-olgae is closely related to G. nivalis, the affinities of G. peshmenii lie with the morphologically dissimilar G. elwesii, and it sits on a different branch of the genus’s phylogenetic tree (the branching tree purporting to describe the evolutionary history of the genus)***. Now I think that a combination of various rather subtle differences make it possibly to distinguish the two species, though not with absolute conviction.

In comparison with G. reginae-olgae, flowering G. peshmenii is generally shorter in stature; the leaf colour is more glaucescent and the outer segments more oblong in outline, with a shorter claw, compared with the typically slender and elegant, often strongly unguiculate G. reginae-olgae. The flowers of G. peshmenii often have a characteristic pyramidal shape, whereas those of G. reginae-olgae are more bulb-like. The most consistent differences, however, are in the shape and markings of the inner segment. The sinus much less pronounced in typical examples of G. peshmenii. Whereas, in G. peshmenii, the apical margin of the inner segment is completely flat, the corresponding margin in G. reginae-olgae is usually slightly flared. Furthermore, whereas the inner segment of G. peshmenii is roughly triangular, with the vertices of the triangle rounded, the inner segments of G. reginae-olgae are usually somewhat constricted near the apex, so that the two lobes either side of the sinus resemble teeth. In pronounced examples, this give the flower a ‘goofy’ appearance. On average the apical mark on the inner segment is smaller in G. peshmenii, and more likely to be V-shaped. It should be noted that these differences are all evident at a population level but that some plants of both species overlap with the other in all the above respects. While it should be possible to cautiously assign an unknown plant to one of the above species, using a combination of all the characters, complete certainty is unlikely.

A quick aside: Galanthophiles (including me) get ridiculously excited over minute variations in the combinations of the various features of snowdrop flowers and this behaviour is thought distinctly odd by non-initiates. No-one, however, finds it strange to admire human faces, nor to attribute the beauty of a particular face to a subtle combination of, say, small nose, full lips and high cheekbones. Just as connoisseurs of human diversity enjoy looking at faces, so galanthophiles appreciate the infinite combinations of stature, shape, colour, markings and other features that the simple snowdrop flower throws up. In fact, it seems highly likely that the facial recognition ‘software’ in human brains is responsible for our ability to detect and remember the tiny differences between snowdrops that excite the admiration of enthusiasts.

Having spent a happy day wandering about in the snowdrop population near Kemer, I returned next to Göynük Canyon, a few miles to the east. On my previous visit, in late October, Cyclamen maritimum had been in full flower but there was no sign whatsoever of G. peshmenii. By late November the Cyclamen was over but the Galanthus was in flower at various elevations from 80m to 600m. Interestingly, the plants at lower elevations were only just coming into flower and all the plants I saw in Göynuk Canyon were less advanced than those above Kemer. I had noticed on my previous trip that Cyclamen maritimum does not go higher than 150m inGöynük, whereas above Kemer it is still abundant at 700m. Whereas there had been plenty of rain near Kemer,Göynük remained bone dry. Clearly there are significant microclimatic differences between these two valleys. The pattern of plants flowering earlier at higher elevations also occurs in G. reginae-olgae on Corfu. Presumably the colder nights and, perhaps, higher rainfall at higher elevations is responsible for this phenomenon. It would be interesting to conduct experiments to resolve the issue. Another time!

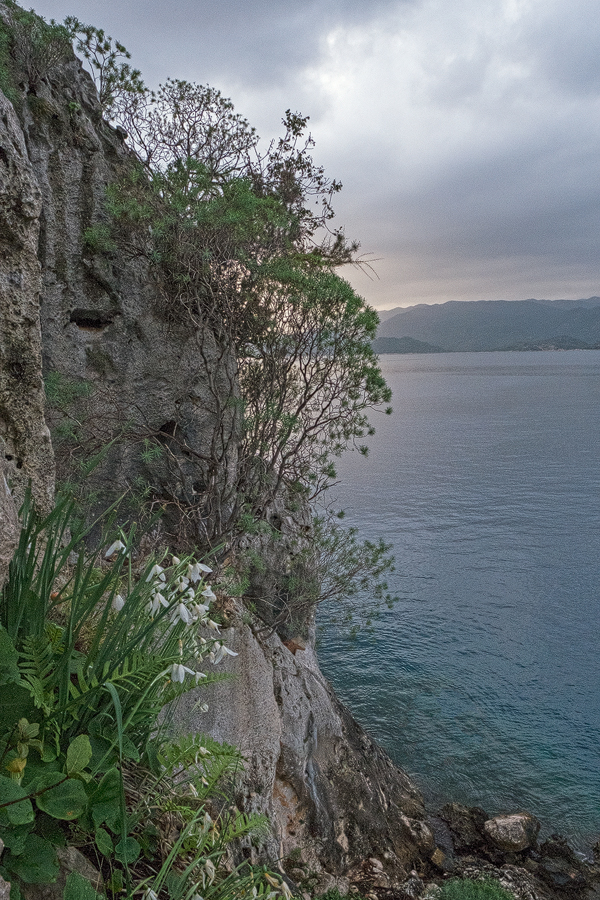

Lovely though the newly opened Galanthus flowers were, especially when seen against the backdrop of the stark limestone mountains, they played second fiddle to a stunning Crocus species, C. wattiorum, which has gone into my book as the prettiest member of this genus that I have ever seen. In a couple of places the two plants were flowering together. I almost died while dangling off a cliff trying to secure a photograph illustrating this magical combination, when a large limestone boulder I had dislodged decided to roll downhill, through me. I would have made a satisfying splash among the tourists milling around on the valley floor, had the gods decided my time was up.

Not enough plants were flowering in Göynuk Canyon for me to form a clear impression as to whether they differed systematically from those near Kemer. The habitat in which they were growing was very different, however: north-facing limestone cliffs, among rocks, far from the river or its tributary streams.

Although seven months travelling constantly in search of snowdrops might seem a long time, in fact there is never remotely enough time to explore as thoroughly as one would like. Presumably, if one were to examine all the patches of suitable habitat in the canyons running from the coastal mountains of this part of Turkey to the Mediterranean, one would find numerous populations of G. peshmenii, but the roads and tracks are few and the terrain difficult to move about in. One of these days I should like to walk the Lycian Way, a clearly marked long-distance trail through these mountains, but that will have to wait for another year****.

It has been known since the 1970s that G. peshmenii occurs on cliffs on the north-facing side of the Greek island of Kastellorizo (Megisti). This outpost of Europe lies just a couple of miles off the Turkish coast at Kaş, an attractive town 150 km to the west of Kemer, not yet utterly wrecked by mass tourism, as Kemer has been. I was curious to see whether I could find Galanthus on the mainland. But a generous and well-informed friend advised me to take a trip out to the small, uninhabited island of Kekova where, he said, I would see snowdrops. To this end I made my way to the marina at Üçağiz and wandered around until I found a boatman willing to ferry me over to the island. Ramazan, skipper of the Koç II (I didn’t care to ask what had happened to the Koç I) took me across the narrow strait and obligingly allowed me to jump ashore at various places to explore.

Approaching the island from the north, the rounded limestone rocks start to assume puzzlingly geometrical shapes. Gradually it becomes clear that one is looking at the remains of an abandoned ancient city, carved into the cliffs and now partially submerged. As we drifted through gin-clear water, the stone walls of ruined buildings were clearly visible beneath the calm surface. Here was a bona fide Atlantis*****, a city sunk beneath the waves. One half expected Patrick Duffy to haul himself onto a rock, wearing 1970s speedos. On shore the signs of this vanished civilisation were everywhere, in stone doorways and niches carved into the rock, where wooden joists had once slotted. Ramazan kept up a running commentary, displaying a particular obsession with cisterns, huge stone caverns that would have been used to capture and store fresh water.

Almost immediately I saw big clumps of G. peshmenii, flowering beautifully in eroded pockets in the limestone cliffs. Ramazan nosed the boat towards a set of ancient steps and I leapt ashore, feeling a bit like Neil Armstrong. Amazingly, some of the snowdrops were growing just a metre or two above sea level, on rocks wet with salt water spray. Closer investigation revealed that the pockets in which the snowdrops grew contained a considerable depth of rich, red soil. A few metres higher up, within the tumbled-down walls of ancient rooms, more snowdrops grew on level ground and here they were still in bud. The population was rather small, but contained within it all the variation I had seen near Kemer.

Also in flower was Narcissus tazetta, which typically flowers in spring but, just like the snowdrops, here occurs in an autumn-flowering form. Daphne gnidioides was festooned with orange fruit and large shrubs of Euphorbia denrdoides mingled with an attractive blue-leafed rue. Growing in exactly the same situation as the Galanthus were big patches of Arisarum vulgare. Dusk was approaching and, reluctantly, I accepted Ramazan’s suggestion that we head back toÜçağiz. The hauntingly beautiful underwater city and its cliff-dwelling snowdrops shall stay in my mind long after the snowdropathon is also ancient history.

* I visited this same colony in February 2015 and saw the leaves at their maximum extent.

** Technically, vernation refers to the manner in which the developing leaves are held together in bud but, for practical purposes, it can be observed by checking the arrangement of new leaves as they emerge from the sheath at the top of the bulb. In Galanthus there are three basic forms of vernation: applanate, in which the leaves are pressed flat against one another, with flat margins; explicative, in which the leaves are held flat against one another but with the margins folded back on themselves; and convolute or supervolute, in which one leaf clasps the other. G. peshmenii exhibits the first of these patterns, but many plants have leaf margins that are slightly or markedly revolute, or rolled back.

*** The relationships among recognised Galanthus species are slowly being clarified by ‘molecular phylogenetics’, the new science of deducing the evolutionary history of groups of organisms by decoding and analysing divergences in short sequences of their DNA. Facinatingly, this is showing that several recognised species, including G. elwesii and G. transcaucasicus are ‘polyphyletic’, which is to say they probably actually comprise several independent lineages, with similar morphologies. The state of the art in this field suggests that G. peshmenii belongs in a ‘clade’, a lineage with a single common ancestor, comprising G. elwesii, G. gracilis, G. cilicicus and G. peshmenii. See Rønsted, Nina, et al. (2013) Snowdrops falling slowly into place: An improved phylogeny for Galanthus (Amaryllidaceae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 69: 205–217.

**** See Clow, Kate (2014) The Lycian Way. Upcountry (Turkey) Ltd.

***** The ancient city of Dolichiste, destroyed by an earthquake in the 2nd century AD.